By Olivia G. Ford

There are always fascinating things to learn – and areas of improvement to identify – at the world's premier HIV research meeting. The 31st Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (CROI 2024) took place in March 2024 as a hybrid conference in Denver, Colorado, and online. Members of The Well Project's team were on hand, in person and virtually, to document findings and other happenings at this unique gathering.

It is extremely well documented in research literature that breast milk is the best food for most babies, satisfying all their nutritional needs while protecting their health and promoting their growth. According to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, benefits of breast/chestfeeding abound for infants as well as their lactating parents. These include lower rates of asthma, obesity, and type 1 diabetes for breastfed infants throughout their lives; and lower rates of hypertension, type 2 diabetes, and several reproductive cancers for their mamas. It is worth noting that these health conditions that can be alleviated by breastfeeding affect Black mamas and babies at higher rates than their white counterparts – just as HIV does. Breast/chestfeeding while on effective HIV drugs has been the standard of care for women and other birthing parents living with HIV in resource-limited areas of the world for many years, and the likelihood of HIV transmission in this way is less than 1 percent.

Some of the posters represent detective work around anomalous cases of HIV acquisition by babies whose nursing parents' viral loads were documented as undetectable.

Now that significant and long-fought-for changes have come to the US Perinatal HIV Clinical Guidelines, US women living with HIV and their babies can more confidently reap the benefits of this "liquid gold." I remain deeply honored and energized to be part of The Well Project's ongoing advocacy and education work in this area – and as a past perinatal health advocate, trained doula, and Black former breastfeeding mama myself, I never miss an opportunity to talk about, and learn about, the magic of breast milk. I was thrilled to see an entire (small, but meaningful!) poster section at CROI 2024 focused on understanding breast milk – specifically, what is or isn't in breast milk in the context of HIV: viral load, drug concentrations, cell-associated virus, and micronutrients. Some of the posters represent detective work around anomalous cases of HIV acquisition by babies whose nursing parents' viral loads were documented as undetectable.

**

The first poster, "Could This Be Cell-Associated Perinatal HIV Transmission?" by Beatrice Cockbain et al, for which I will provide just a brief overview, looked not at breast milk directly but at cell-associated HIV transmission, considered a potential mode of infant acquisition through pregnancy and birth as well as through breast/chestfeeding. One of the cases in the poster's literature review was from the DolPHIN-2 study, in which one infant seroconverted late after remaining HIV-negative during exclusive breastfeeding by a mom whose viral load was undetectable, then transitioning to mixed feeding. In this case, maternal microchimerism (when genetically distinct cell populations from two different individuals are found in one person – here, a baby and their mom) in the baby's gut was the potential explanation for their acquisition of HIV. The review concluded that viral suppression for parents, as well as preventive medication for babies, were likely protective from these rare occurrences.

**

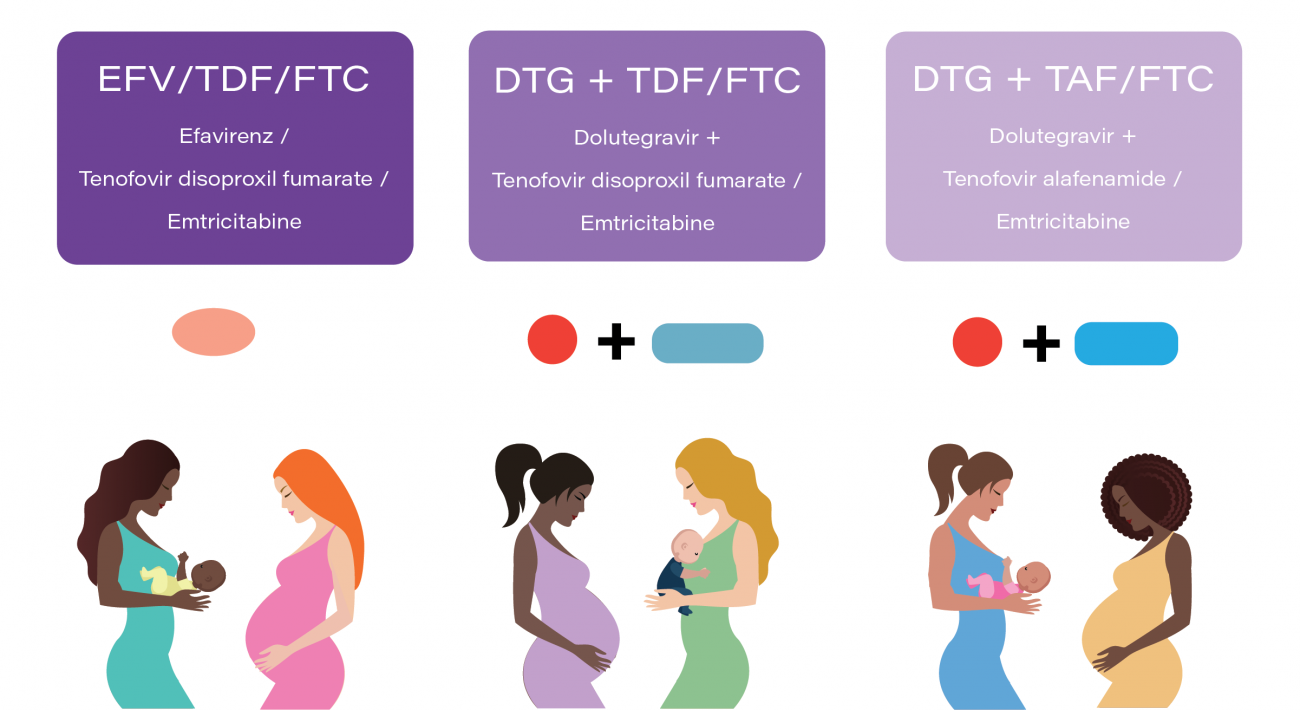

Transfer of HIV drugs from parents to their nursing babies was the subject of another poster, by Tk Nguyen and colleagues, titled "Breast Milk Transfer and Infant Exposures to DTG, TAF, and TFV." Researchers looked at levels of three widely used HIV drugs – dolutegravir (Tivicay, DTG), tenofovir alafenamide (Vemlidy, TAF), and tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (Viread, TDF, TFV) – in the breast milk and plasma of 192 parents and the plasma of their 192 paired infants. This poster represents one of numerous analyses to come from IMPAACT 2010 (the VESTED Study) since its primary results were released in March 2021. IMPAACT 2010 is a phase 3, open-label study that enrolled pregnant women living with HIV who were randomized to one of three study "arms" to take either:

- DTG + TDF/FTC;

- DTG + TAF/FTC; or

- efavirenz (Sustiva, Stocrin, EFV)/TDF/FTC

The VESTED study looked at safety and efficacy of these regimens during pregnancy and through 50 weeks of parent and infant follow-up after birth. All three were found to be safe and highly effective during pregnancy, though women were more likely to have their viral loads jump to 200 copies/mL or above (considered "virologic failure") while taking EFV than on DTG. Parent/baby pairs for this analysis were only drawn from the DTG arms.

Participants came from six countries in this analysis, with the vast majority (80 percent) hailing from Zimbabwe and Uganda. They were enrolled in the study between the end of first and end of second trimester of pregnancy (14 to 28 weeks), and the average age of parents at that time was 26. Median age of babies at birth was full term (40 gestational weeks); median weight at birth was the equivalent of 6.8 pounds (3,089 grams). Samples for this analysis were taken at week 6 after parents gave birth (postpartum).

Researchers estimated the relative infant dose (RID) for DTG, TAF, and TDF using a target feeding volume of 150 mL/kg per day and concentrations of the drugs in breast milk. For context, the classification system detailed in the textbook Drugs and Human Lactation regards an RID of less than 10 percent of maternal dosage as acceptable; RID of a drug is considered unacceptable when it climbs above 25 percent. In this study, the estimated median RID from breastfeeding for DTG was 1.92 percent; for TAF and TDF, estimated RID was nearly zero.

Based on these findings, transfer of these drugs through lactation is low, meaning minimal systemic exposure for babies who are predominantly breastfed. The significance of these low (subtherapeutic) drug concentrations is unknown, but ought to be taken into account in the context of potential drug resistance in the event that an infant is diagnosed with HIV while breast/chestfeeding.

**

An HIV diagnosis is not just a little star on a chart on a conference poster. Even with effective treatment, it is a life-changing event for the kids as well as the moms.

On the topic of infant HIV acquisition, a third poster featured a substudy of another trial brought to us by IMPAACT: the IMPAACT PROMISE 1077BF perinatal HIV trial. The "Breast Milk Reservoir, Tenofovir Levels, and HIV Transmission Among Breastfeeding Mothers" substudy assessed the association of infant HIV acquisition with viral load, as well as concentrations of TDF, in parents' plasma and breast milk. Maxsensia Owor et al prefaced their analysis by noting instances in which HIV has been detected in a parent's breast milk when their plasma viral load was undetectable. The question appeared to be: Could this discordant scenario account for the rare cases of vertical transmission when a parent's viral load was documented as undetectable? This is a key vexation of the PROMISE studies: Of thousands of mom-baby pairs, two babies in the study acquired HIV in this way.

In this substudy, a case group of 31 mother-baby pairs in which the baby had had a positive HIV test was matched with a control group of 62 pairs (1:2 matching) in which the baby remained HIV-negative. The pairs were matched according to study site, birthing parent age, infant assigned sex, and whether or not they had been randomized to the postpartum (mom receiving TDF-based HIV drug regimen or infant receiving a preventive HIV drug after birth) or the antepartum (long-term follow-up through pregnancy) component of the larger study. The median age at which infants in the case group acquired HIV was six months.

In a nutshell, the substudy concluded that higher viral load and lower concentrations of tenofovir in moms' plasma and breast milk were associated with higher likelihood of infant HIV acquisition through breastfeeding. Those odds increased (2.6 times for plasma viral load; 1.8 times for virus in breast milk) with every ten-fold increase in viral load. But after squinting at this and related posters for quite a while, I am concluding that the initial framing of this analysis is a bit misleading.

The case group does not actually include any documented cases of vertical transmission while a parent's plasma viral load was undetectable. In fact, the spread of maternal plasma viral load in the case group was 4,822 to 124,886 copies/mL, with a median viral load of 39,228 – definitively detectable all around. Median plasma viral load in the control group was 20, and only seven control-group mamas had breast milk viral load above the lower limit of quantification (200 copies/mL for RNA viral load in breast milk in this study). Further, just 21 percent of parents in the case group who were on TDF had detectable levels of the drug in their plasma or breast milk, compared with 84 percent in plasma and 78 percent in breast milk in the control group.

These findings call to mind that old treatment-as-prevention (TasP) adage: TasP works when people can get the drugs into their bodies. They re-assert the fact that adherence is paramount, to keep those viral loads down as low as possible to avoid transmission during breast/chestfeeding. This was among the conclusions in another PROMISE secondary analysis from 2018 that looked at impact of maternal viral load and CD4 count on breastfeeding transmission and highlighted those two not fully explained cases mentioned above. Hopefully, from a clinician-researcher's perspective, looking at these variables brings us closer to understanding those rare infant acquisitions with undetectable viral load.

I also want to pause and name the fact that these 31 little ones, and all the kiddos in these studies who became HIV-positive, are now Dandelions. An HIV diagnosis is not just a little star on a chart on a conference poster. Even with effective treatment, it is a life-changing event for the kids as well as the moms, who I am sure were not hoping for this outcome. The same is true for the two babies who acquired HIV when their moms' documented viral load was undetectable. It is indeed crucial to try and ascertain what occurred in those instances so as to prevent whatever happened from occurring again – but two babies out of 2,431 are still strong odds in favor of feeding a baby from one's body when on HIV drugs if they choose.

**

There are things humans get from breast/chestfeeding that they cannot get anywhere else.

To that point, I'll close with a nod to the last of the four posters in this session, "Metabolomic Perturbations of Tryptophan & Arginine Metabolites in the Breast Milk of Women With HIV" – quite a mouthful. Nicole H. Tobin and colleagues looked at samples of breast milk from a large study conducted in Zambia from 2001 to 2008. Samples were from women living with HIV whose babies did not acquire HIV, as well as women who were not living with HIV. The researchers conducted untargeted metabolomic analyses on the samples – meaning they looked for any metabolites (molecules involved in chemical processes in the body's cells) they could detect, rather than seeking specific compounds. Amid the more than 700 biochemicals they identified, they were looking for those with levels that were much higher or lower (differentially abundant) among women living with HIV than women without HIV. This was before effective HIV drugs were available in Zambia, so the overall study had looked at whether breastfeeding helped babies survive (it did).

Researchers found tryptophan levels to be significantly lower in the milk of women living with HIV than those without HIV at all time points from one week to 18 months after birth. Tryptophan is an essential amino acid that is vital for infant immune and neurocognitive development, as well as growth. For infants, breast milk is the only source of this essential nutrient, so these findings may contribute to understanding health concerns in babies born to women living with HIV.

I highlight this study not necessarily for the relevance of its findings to today – this was a different era, and the effects observed in this study could have been from untreated HIV – but because it lifts up the fact that there are things humans get from breast/chestfeeding that they cannot get anywhere else. Beyond bonding, bodily autonomy, avoiding the cost of formula, and other benefits, what is actually in breast milk provides essential components that can aid babies' development and stave off illness. Let's keep that top of mind in our advocacy, and keep finding ways to learn about the immense value of this food only humans can make.

More from The Well Project on the 31st Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (CROI 2024)

- Unpacking the Latest in HIV Research and Community Engagement: An Overview from CROI 2024 by Bridgette Picou LVN, ACLPN

- We Could Stop a Cancer-Causing Virus in Women – But Will We? A Recap from CROI 2024 by Bridgette Picou, LVN, ACLPN

- Key Community Takeaways From CROI 2024 (HIV.gov)