December 1, 2023 – New York Magazine.

By Vivian Manning-Schaffel, a journalist covering entertainment, culture, psychology, and health.

After a raucous rendition of "Holiday" on Madonna's current Celebration tour, one of her dancers collapses. She covers him with a sheet, then launches into a thoughtful rendition of "Live to Tell," rising above the audience in a makeshift frame, honoring those who fell to AIDS with a moving tribute created in partnership with the AIDS Memorial. Portraits of the fallen, including her friend Martin Burgoyne, Sylvester, Keith Haring, and a sprinkle of women including Cookie Mueller, unfurl on enormous screens. As the song progresses, the images multiply, yearbook-style, depicting the sheer volume of people lost to the epidemic.

In recent years, celebrities like Jonathan Van Ness and Billy Porter have disclosed their status, yet what we see about women with HIV-AIDS in the media landscape is sorely lacking. Globally, women and girls make up more than half of the 37.7 million people living with HIV, acquiring the disease at a higher rate than men. Annual HIV infections in the U.S. remain stable, but new infections disproportionately affect Black women at 11 times that of white women, and four times that of Latinx women. Trans women have 49 times the odds of having HIV compared to the general population in the U.S.

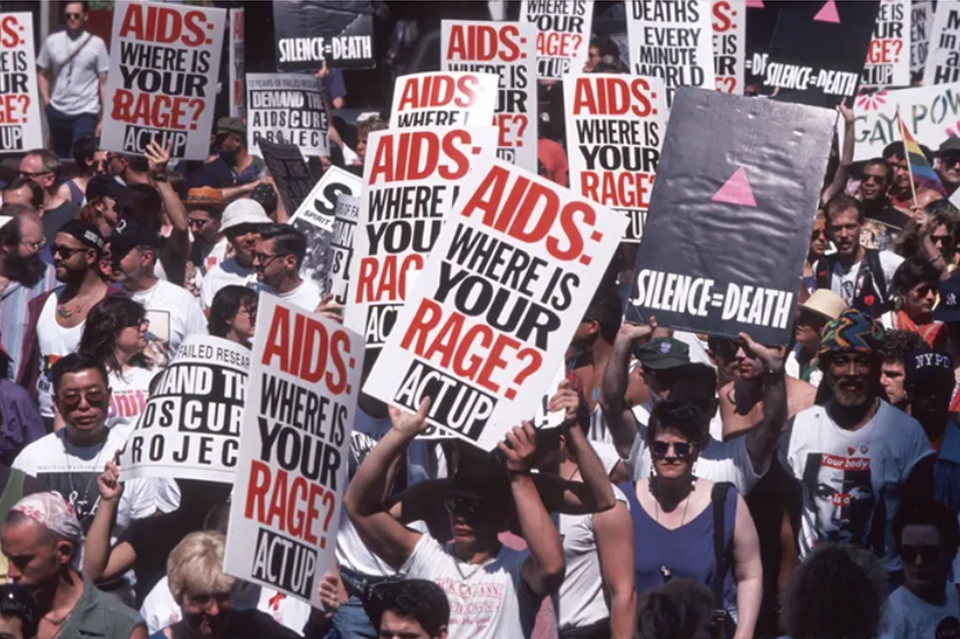

As someone who came of age during the height of the AIDS crisis, I knew enough about AIDS to be terrified of unprotected sex, but doctors didn't consider me to be at risk; the HIV-positive friends I have and lost to AIDS were gay men. Sarah Schulman, activist and author of Let The Record Show: A Political History of ACT UP New York 1987–1993, told me, "Women were only seen as vectors of infection at first, to children and later, to men." Many of these women, she adds, were often low-income people of color who died very quickly. "They got diagnosed much later because they were either poor and had worse health care or they were taking care of everybody else and didn't get to take care of themselves."

With tremendous advancements, HIV-AIDS is now considered a chronic disease, but research and messaging still largely exclude women. You can't watch a Real Housewives episode without seeing countless ads for HIV treatment meds, like Cabenuva and Biktarvy, which include women in their narratives, but despite recent CDC literature claiming "PrEP (Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis) Is for Women," those ads are still focused on gay male and trans female–male couples. This exclusion throughout systems has driven many positive women to activism. But ending AIDS by 2030 seems out of reach as 1.3 million people were newly infected in 2022, and it will likely remain that way.

On the 35th anniversary of World AIDS Day, eight thriving HIV-AIDS survivors and activists diagnosed between the 1980s and 2000s lend some perspective to living with the disease long-term; among them six Black women (one trans), and two white women, share their experiences with health care and stigma.

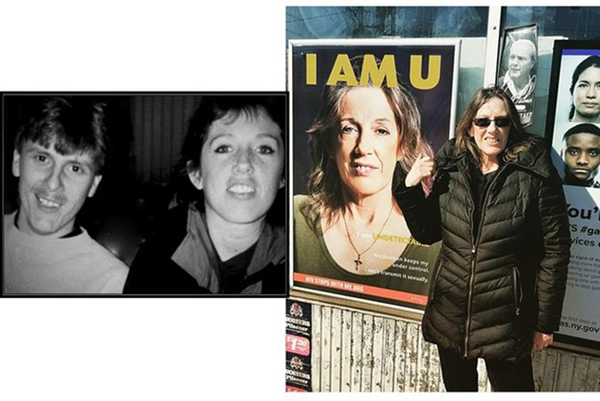

Nancy Duncan, 66, Long Island, New York

Diagnosed: 1990, age 33

On her diagnosis: I contracted HIV through unprotected sex with a man I dated after my marriage ended, in 1985. He didn't know he was positive. I felt very scared and alone and didn't know anyone else living with HIV. I went to an AIDS-designated hospital for treatment in my county and didn't like the way I was treated there. It wasn't until I started attending an HIV support group and meeting other people in my situation who told me about a better clinic. Now I've had the same HIV doctor for around 30 years. There was no internet so I had to rely on books and networking with other people to acquire information.

On her path to activism: I've done a few actions with ACT UP NY and Planned Parenthood, whom I worked with for many years. I have done many legislative visits through AIDS Watch in Washington, D.C., and on a local level as well. I became public with my HIV status in 1999 when I started sharing my story in schools all over my county. I felt as though I was helping others not to get HIV. Several magazines did my story with photos. I also did the New York State Department of Health "HIV Stops With Me" spokesmodel campaign for three years and had my face on billboards for HIV awareness and stigma prevention. My son, family members, and friends are all supportive and proud of me.

Marissa Gonzalez, 34, Lehigh Acres, Florida

Diagnosed: 2016, age 26

On health care: At one point this clinic was like home and it's sad to see how much their focus on patients has changed. Over the course of 12 months, I've seen three different doctors. In my area, a large health-care system no longer offers HIV care, and, quite honestly, the ones I've been to have been lacking. I emailed their Medical Director in August but have had no response. Yesterday, I called for a sick visit and still have not received a call. Providers don't listen to their patients. Treatment options often aren't discussed as a collaborative effort to determine what's best for the individual and their lifestyle. Staff can be judgmental and rude, which is harmful in a space that is meant to feel safe.

On stigma: I had been bullied all my life; the very reason I attempted suicide is ultimately the reason I chose to be public, so HIV couldn't be used as a weapon against me. I volunteered for a local youth group and hosted an event for teen girls on HIV-AIDS Awareness Day and a woman who was born positive said, "What would you know about living with HIV?" From that moment, I knew I couldn't be silent anymore. I shared a status on Facebook outing myself and was met with a lot of sympathy and support. Until HIV is talked about in extended sexual health curriculums in schools, more focus is put on HIV in medical school, and conversations, testing, and treatment are normalized among families and partners, there is still a very long way to go.

Michelle Lopez, 56, Brooklyn, New York

Diagnosed: 1991, age 24

On her diagnosis: I acquired HIV through unprotected sex with my daughter's father in 1989. He never told me. I disclosed that his daughter and I tested positive and he should get tested. He said: "Ain't life a bitch. I have been dealing with this a long time!" When I was diagnosed, I was undocumented and living with a man who was beating the shit out of me because he promised he was going to marry me and get me my green card. This one night was the worst beating, but it was the best because I left. I got on the train in Queens at night and just switched until morning, ending up in Brooklyn. I saw an ad on the train and I swear, it spoke to me. I got off the train, called the ad, and broke down. This lady said, "Where are you right now?" I'm standing at the corner of Flatbush Avenue and Nevins Street. Right away the woman said, "Miss, I want you to turn around where you're standing and I want you to walk into Nevins Street facing west. You're going to find me." They were five blocks from where I was standing.

On her path to activism: I was involved with ACT UP NY. Women needed to be able to get into clinical trials so at least some of us could die at least getting some kind of care and benefits. In 1996, Oprah Winfrey did a show on my life. It was not an AIDS-related show. It was called "Best Friends" — I put mine in a living will to parent my kids, because back then they were telling us you're going to die. After receiving legal status, I worked in public health as a peer, doing outreach work and referring people to be tested. Right now I work as a consultant for Einstein Rockefeller CUNY Center for AIDS Research and sit on different committees to do research, looking at the impact of HIV and AIDS. I became a treatment advocate all the way to Washington, D.C. as a member of the NIH AIDS Clinical Trials Group Community Consistency Group. We created an educational module called U=U, undetectable equals untransmittable. Our module literally teaches providers how to meet us where we're at — we're giving them a definition of what U=U means to us...

Continue reading this article in New York Magazine's The Cut